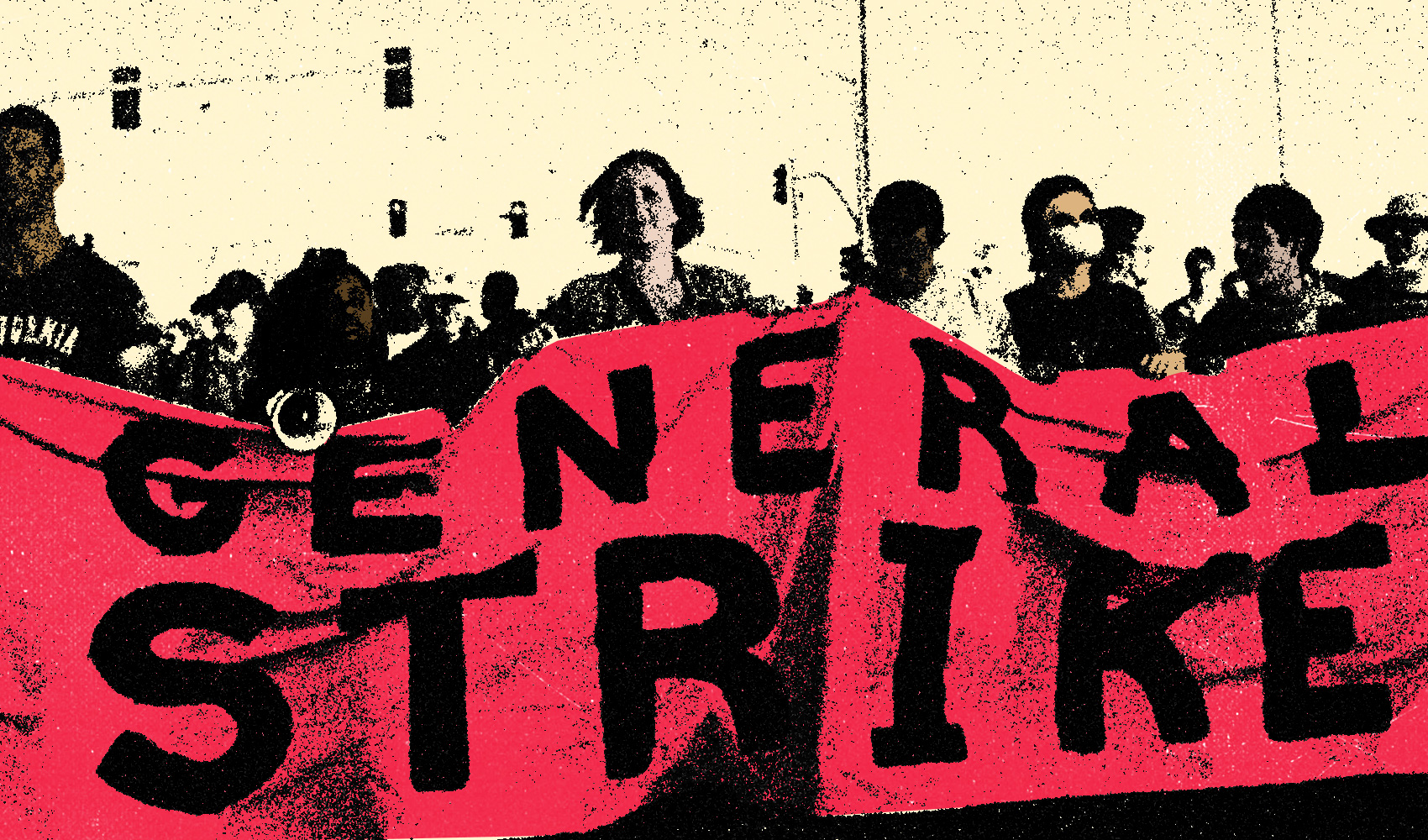

January 30th has been set as a nationwide day of action against the campaign of state terror carried out by ICE and other DHS agencies. Some have referred to the 30th as a ‘general strike’.

In this article, Black Rose/Rosa Negra member Cameron Pádraig examines the prospects for a general strike on the 30th, offering a critical perspective while encouraging organizers and others to use it as a jumping off point.

by Cameron Pádraig

Intensifying class conflict here in the United States, now taking place in the context of a widening revulsion at racialized terror in the Twin Cities and other major metropolitan regions, has put the notion of the general strike back into circulation in a major way. January 30th has now emerged as the date on which a national general strike is set to take place. However, with its lack of coordination, specific demands, or backing from unions there’s little chance that the 30th will see a general strike worthy of the name. How then, should we relate to or intervene in it?

General strikes loom large in the left’s imagination. This is particularly true of a US left contending with decades of eroding union density and acquiescence by the labor movement to the inclusion of no-strike clauses in virtually all contracts. At the same time, the living historical memory of the (relatively) more common mass, militant, and rank-and-file led strike actions of the previous century is fading with the aging population who experienced or organized them.

It’s no wonder that the general strike has taken on a mystical quality. This is true both in the sense that it’s regularly invoked as a panacea for confronting a wide range of social problems, and in mystifications about what a general strike actually is, or what organizing one looks like. As Joe Burns notes, the last 15 years have seen calls for a general strike regularly proliferate across social media, but almost never undertaken as serious organizing efforts or involve participation from unions. Most are reduced to single day consumer boycotts, a noble effort, but one that pales when compared to the scale and type of activity called for by a general strike.

The most notable 21st century instance of a mass strike was the ‘day without immigrants’ in 2006, when organizers with deep roots in immigrant communities managed to galvanize a one-day work stoppage, bringing over five million people onto the streets of 160 US cities. Another can be found in the 2011 Oakland general strike initiated by the Occupy movement with at least some backing from local unions. Still, no serious general strike has happened in the US in nearly 100 years.

Despite widespread confusion around the specifics of what makes a general strike a strike—namely, the organized and sustained withdrawal of labor as a means to force concessions from an adversary—its staying power as a concept shows the widely held, even if often shallow, recognition of its potential as one of the few real ways to push against the state and capital. In other words, people reach for the strike weapon because we know intuitively that by collectively slowing or shutting down the economy, we are inflicting pain on those who occupy positions of power within capitalist society’s structures of domination.

Strikes expose fundamental conflicts at the heart of capitalist social relations by interrupting the everyday processes through which exploitation is normalized and reproduced. By halting production, circulation, or service provision, strikes make visible the antagonistic relationship between labor and capital that is otherwise obscured by everyday routines, ideologies, and legal frameworks. For militants working to build an infrastructure for working-class radical politics, it is important to be clear about the distinctions between different kinds of strikes, their aims, and their limits. This clarity matters even as we recognize that real struggles are often messy, uneven, and shaped by immediate conditions rather than theoretical purity.

Interest in the general strike as a serious social weapon has grown rapidly in recent weeks as a response to the escalating campaign of racialized state terror being exacted by the Department of Homeland Security and various agencies under its umbrella. The federal occupation of Minneapolis, and especially the ICE murder of Renée Nicole Good, pushed organized residents to think seriously about what an escalation of their own might look like. This manifested in January 23rd’s ‘ICE OUT: Day of Truth and Freedom’ action.

Initially proposed by a coalition of religious, NGO, and community groups, unions eventually signed on to the call for a day of mass action on the 23rd, lending credence to claims ahead of the date that this had the makings of a general strike. But constrained by contracts bearing no-strike clauses, unions did not take strike votes or call for work stoppages, instead only indirectly suggesting that their members use PTO or call out for the day. This was a necessary—and seemingly successful—short-term workaround given the circumstances, but it also made clear that there was a line the union brass was not willing to step over. Until rank-and-file workers, including those already in unions, have the independent power to decide when it’s time to strike, any attempt at something on the scale of a general strike will face serious obstacles.

With an estimated 50,000–100,000 people in the streets of Minneapolis on the 23rd, it’s hard to argue that it was anything but a success—whether or not it met the specific criteria of a general strike. Only days after the mass action on the 23rd, however, federal agents murdered Alex Pretti in cold blood. With the shock of yet another execution by federal agents still fresh, student organizations at the University of Minnesota put out the call for a follow up mass action, this time on January 30th and on a national scale. Hundreds of community groups, NGOs, political organizations, and others have now signed on to the call for a “nationwide shutdown”. We can take this as a positive sign, while still recognizing that it will fall short of achieving its stated aim of initiating a general strike.

At the same time, it’s critical to understand that our first task isn’t to dampen the embers of a genuine desire to fight back with pedantry about what a “true” general strike is. Instead, we should work to animate interest in the tactic and its history, while simultaneously encouraging reflection on the limitations and contradictions of the mass actions that are being called ‘general strikes’. Finally, and most importantly, we need to be ready with suggestions for where organizing might go next.

The national day of action on January 30th won’t be a general strike, but that shouldn’t mean we have to write it off or deride it as pointless. It gives us an opportunity to invite our coworkers, neighbors, or classmates into the streets with us, opening the door to conversations about how we can bring the fight back into our workplaces, neighborhoods, and schools. Keeping those conversations going is a first step on the path toward organization—the prerequisite for anything as ambitious, and as necessary, as a general strike.

Cameron Pádraig is a rank-and-file member of UAW and a member of Black Rose/Rosa Negra’s Bay Area Local.

If you enjoyed this article, we recommend Organizing to Keep ICE Out of Your Workplace and Healthcare Workers Freed a Patient from ICE – You Can Do the Same