On January 13th, the Syrian Transitional Government launched a major offensive on the territories under control of the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North East Syria (DAANES) – the first it has faced since the defeat of ISIS.

To better understand the situation and its implications for DAANES, members of Black Rose/Rosa Negra’s International Relations Committee spoke with Irma, an internationalist volunteer from the US who spent years in the military and civilian structures of the Autonomous Administration.

Please note that this interview took place over the course of several days, while Irma was in transit. The situation on the ground changed numerous times during the course of our discussion and likely will have again by the time you are reading it.

This interview has been edited for clarity, but its original conversational tone has been left unaltered.

Black Rose/Rosa Negra – International Relations Committee (BRRN – IRC): Could you start by giving a short personal background?

IRMA: Yes. My name is Irma. I’m a woman from the east coast of the so-called United States, and I’ve spent several years in the Women’s Defense Units of YPJ in Rojava, mostly working as a medic. I spent a short time doing civil society work, as well as working with Jineolji1 while living in the women’s village of Jinwar.

BRRN – IRC: There have been significant developments in Syria over the last month and a half. Can you provide a broad overview of the situation?

IRMA: I think we can start with a bit of a narrow lens and then zoom out a bit. So since the fall of the Assad regime, the Syrian Transitional Government (STG), being ruled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS),2 with President Jolani, also known as al-Sharaa,3 has been trying to legitimize and institutionalize itself, now with major backing by the EU, by the UK, by France, by the United States, by Israel, and especially by Turkey.

They’re launching major attacks on the regions of Syria which have seen revolution, areas which are under the control of the Autonomous Administration. Their claim is that these are Arab regions, and thus they don’t belong to the Kurds. However, in a place like Syria, it being in the region of the world which birthed civilization, there is no place that we will find just one people, just one nation, one ethnicity, living there. This is why the Kurds also don’t adopt the name of Rojava in an official way. It’s called the ‘North and East Syria’ because it’s multi-ethnic ethnic, the system of governance is built upon the foundation of a multicultural region.

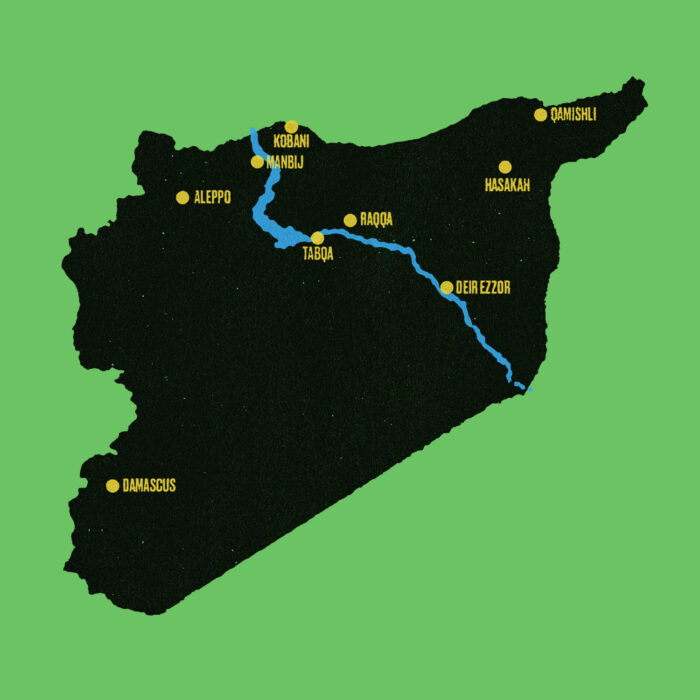

Last year, HTS brutally attacked and took over the regions of Manbij and Shahba, meanwhile, in southern Syria, they were committing massacres against the Druze and in the Western coast they were massacring Alawites. This year, they’ve encircled and attacked two majority-Kurdish neighborhoods of Aleppo: Ashrafiya and Sheik Maqsood. They then began moving east, brutally attacking and occupying Tabqa, Dayr Hafir, reaching the city of Raqqa, then the entire region of Deir Ezzor, and all the way up into Hasakah.

I know these are a lot of names, but it’s important to know that each of these places are strategic. Tabqa, as well as Tishreen which is just a few kilometers down the river, are cities that were built around dams. These Dams bring most of the water and electricity to Syria.

Raqqa was the previous capital of the ISIS caliphate. Deir Ezzor provides a strategic location, holding the main routes from Iran to western Syria, as well as having most of Syria’s oil.

There is now pressure on Kobani as well. This is the place that we all know that YPG and especially the women of YPJ, historically liberated from ISIS in 2015 and now this place is once again completely encircled by the same forces, just under a different name. The water, the electricity, the internet has been cut off in Kobani for over two weeks now.

HTS forces are taking over more land, cities, resources, and freeing more and more ISIS prisoners from the prisons that were once under control of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).4 Every day that we’re looking at a current map of Syria, the regions of the Autonomous Administration are becoming smaller and smaller. Now, it doesn’t even look like a region. It looks like small islands.

So what I’m trying to say with this is that it’s not just a military conflict that’s happening. It’s a war of liquidation. It’s an existential crisis of land, peoples, and a revolutionary project.

If we take a broader view, we can also see how the current developments reflect a shifting balance of power in the region, and are signaling the onset of a new political phase in the Middle East. A major indication of this shift came on January 5th and 6th—the same days that saw initial attacks on the neighborhoods in Aleppo—when a meeting took place between the Syrian Transitional Government (STG), Israel, and the Turkish foreign minister. The meeting received support from the US, France, Britain, and the EU.

In this meeting, the STG and Israel agreed on a joint communication mechanism under US supervision. In other words, this meeting saw the formation of an alliance against the Autonomous Administration. Political support was being declared for the new Syrian regime, and the okay was given to liquidate the Autonomous Administration regions and areas of the Rojava revolution.

In this sense, the attack on Rojava by the STG is not an isolated event, it’s part of a larger coordinated approach between al-Sharaa regime and the West.

But what do all of these different countries with different desires get out of this specific deal?

Israel genuinely wants Syria to remain fragmented. Turkey, meanwhile, is wanting a Syrian administration that’s loyal to it in order to implement neo-Ottomanism throughout the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean. The Gulf States and Britain want to establish a sphere of influence in the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean through HTS. The most influential of these powers, the United States, wants to establish a balance among all of these countries, all of which are its allies. Ultimately, all parties are likely to take a position close to Israel’s arguments.

We can see that since the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011, the goal of the United States and its allies had been to overthrow the Assad regime and install a pro-Western government. Now, that goal has been more or less achieved with this Transitional Government. HTS on its own was not able to overcome the Assad regime, it is a force that was built up with a lot of preparation by the United Kingdom and Turkey.

So now that they are in power, there’s a government in Damascus that has been fully integrated into the US and the Western led reorganization project. HTS fully accepts the rules of capitalist modernity. It’s economically integrated into the Western camp. It recognizes Israeli hegemony, evidenced by its silence on the Israeli occupation of parts of southern Syria.

BRRN – IRC: There is some question about what role the US has played historically in relation to the Autonomous Administration. Could you describe how this has changed over time, especially recently?

IRMA: When the US allied itself with the Kurds over a decade ago now, they were under attack from ISIS, and Assad was still in power. So the tactical alliance that they had with the Kurds was driven by, we can say, three major motives.

First, cooperation with YPG offered a way for the US to gain military prestige in the fight against ISIS. Second, the US pursued the goal of bringing the revolution under control, limiting its socialist orientation and steering it more into a nationalist direction. Finally, the Kurds served as a means of exerting pressure on the Assad regime and the Russia-Iran bloc.

Now, today, there is a serious change in relations with the SDF. With HTS now in power as the STG, the US has lent it more and more support, and the relationship with SDF is no longer needed.

Previously, the US tried to control these tactical military relations in Syria from east of the Euphrates. But now it no longer needs to do that. Now it’s trying to implement its political and diplomatic strategy through Damascus, through the state.

This is also why we can say that if you are a supporter of the Rojava Revolution in the US, putting pressure on your politicians in this situation will not work. Because the US has no more use for the SDF; all it cares to see is steering it away from its socialist revolutionary line and toward full integration into the new regime. In other words, the US wants to see the elimination of the social revolution and the Autonomous Administration.

Additionally, we have to also analyze this division happening between the Kurds and Arabs in Syria in a similar geopolitical way. Turkey has systematically been creating division between the peoples of the region and weaponizing it against the peace process. Every time that the STG and the SDF were about to come to an agreement on something, the Turkish mediators would intervene and not allow it to proceed.

These building tensions between Arabs and Kurds are not a natural tension between peoples. These are peoples that have been living together in these regions for hundreds of years, and now we’re being fed this media line that the tensions, the fighting, is due to innate racism. But what’s actually happening is a political attack against the project of the democratic nation—a nation of many peoples, many ethnicities, cultures and languages.5 This is what’s being attacked. The point is to destroy this attempt at democratization of the region.

What’s happening is Turkey, Israel, and the U.S. believe if they can make the attacks from HTS seem racialized, then they can both hide their own political incentives for these attacks as well as destroy the brotherhood that has existed between these peoples in this region.

It has to be very well known that Jolani or al Sharaa does not represent the will of the Arab people in this situation, nor do the people that fight for him represent the will of the Arab people. What he represents is the will of the Western capitalist hegemonic powers.

It’s important that we break this rhetoric that’s making division between the ethnicities in the region, and to do so we must have an analysis of the forces at play, both locally and geopolitically.

BRRN – IRC: How have the Autonomous Administration, and the peoples of North East Syria, reacted to these threats?

IRMA: At the risk of really generalizing a situation that is very complex and has many, many years of historical precedent, I’ll begin by saying that the Autonomous Administration and the SDF, since the beginning of the regime change, have had a diplomatic approach, while the same time preparing to defend themselves. Now, with this peace process, the Autonomous Administration is trying to find common ground with the STG, to reach an agreement and to avoid war.

This approach, we have to understand, is a strategic approach. It’s not tactical. To illustrate my point through contrast, we can take the alliance that the Autonomous Administration made with the U.S. as an example. That was a tactical alliance. It was not strategic. It wasn’t part of a revolutionary process. It was purely in order to secure the ability for self defense in the face of ISIS attacks.

But the relationship that’s being built in the peace process in Turkey,6 as well as the process that was being built in the last year with the new Syrian transitional government is different. These are strategic moves. They are part of a strategy aimed at trying to move towards a more free life, not just for the regions where the revolutionary forces are present, but for all of Syria, for all of the Middle East.

Now, a lot of people are really wanting the SDF to just fight against Turkey, to fight against HTS, even to fight against the United States, to make this fight for ideological reasons.

The Autonomous Administration and SDF could easily say, “hey, you are this dominating force, you are this oppressive force against freedom of many people, and we want to overcome you by military action.”

But they don’t. Why is this?

Instead, what they say is, “we want to overcome you by democratization.” Because otherwise, the Autonomous Administration, the SDF, and the other revolutionary forces in the region would be at war with everyone around them all the time. Faced with this reality they say, “let’s join hands. Let’s promise not to harm each other. Let’s find a way that we can live together and build democracy.”

Of course, there is an extremely delicate balance to be struck between learning to co-exist and keeping a sense of dignity. The latter requires thinking carefully about when to apply self defense in order to maintain the gains that have been brought into existence by the sacrifices of many, many people.

So of course, this is a very long and brutal process, but it’s one that must take place in order to build the kind of world that is envisioned by this revolution. This is the same process of how the Autonomous Administration was built up in the first place. Not everyone was convinced of this project, the democratization of a region, this kind of revolution. It takes many, many years and lots of effort.

Anyway, I digress.

For over a year, the Autonomous Administration and the SDF have been in discussion with STG to try to reach these agreements on how to live together. For the Autonomous Administration, there were some things that were full red lines. For example: women’s autonomy. This was not something to be debated. The right to autonomous self defense, this was not something on the table either. These types of foundations of a free life are central and were never up for discussion.

So at the same time, the STG were also making a lot of promises that they weren’t keeping and they’re beginning to take military action that required the SDF to respond. These different actions and processes were overlapping and often contradictory. While one thing was being said in the negotiating room, another thing was happening on the ground in military terms. Today we see this happening exactly the same way, with the cease fire agreement that has been broken over and over by the STG the same day that it was that it was agreed upon.

This back and forth came to an end on January 19 when there was a meeting between Jolani and Mazloum Abdi.7 The STG’s demand was that the Autonomous Administration essentially surrender and give up the revolutionary achievements. They wanted the SDF to lay down their arms and fully integrate into the Syrian state army. They wanted all of the regions outside of some of the cities in Jazira Canton, for example, like Derik and Qamishli, to be under their control. They were ready to take all of the rights away from women. For all of this, they also offered to Mouzlam Abdi the possibility of becoming governor of Hasakah, which he refused.

And so the Autonomous Administration and the SDF responded to this by calling on everyone in the society to prepare for revolutionary people’s war, a full mobilization of the society.

They said: “we will resist everywhere.” They called on all four parts of Kurdistan to come, to break down the borders, to join the defense. They called on every youth in their society to pick up a weapon, every civil structure to turn into a military unit, and this is exactly what we saw happen.

Now, on the one hand, this served as a major boost in morale. It seemed as if people were saying “finally, we have this moment that we can just fight back.”

At the same time, it was very frightening. It was very frightening that we got to this level of full on self defense. That really, really meant that there is a crisis of existence happening.

The society responded to the calls for a full mobilization with exactly that. We saw 1000s of people rush the borders of Turkey. They were breaking the walls down. They were burning down the checkpoints. I mean, even today, they’re still doing things like this. These protests are going on, they’ve become so intense that also the Turkish police and the Turkish military are shooting down the protesters and killing them.

In Başûr, southern Kurdistan, the borders of Iraq also were being pressured to open. Vans full of Kurdish youth were crossing to join the resistance, were sending humanitarian aid. There were hundreds of fighters coming to cross the border to join the defense. We saw images and videos of people everywhere declaring their preparedness for the situation.

They were mothers and grandmothers that were picking up weapons. There were wounded fighters still in their wheelchairs that were creating military units and were declaring their preparation to fight.

It is a full mobilization.

I mean, even now, just thinking about it, it makes me emotional, seeing these videos of these grandmothers seeing these videos of these wounded friends who have already given so much to the revolutionary fight. I’m moved both by their level of courage, but I have this feeling of being ashamed that they would ever have to pick up a weapon again after they’ve already made such huge sacrifices.

BRRN – IRC: To return to something you spoke to earlier, it seems clear now that the SDF has suffered large scale defections by Arab tribespeople who had previously been incorporated into the structure of the militia. Can you explain what precipitated this?

IRMA: When we look at the fact that so many Arab tribes have defected at the onset of this most recent war, if we look at it in isolation, no doubt it raises a lot of questions.

But if we look at it, if we look at the situation as a part of a long term project, we can see how this is the direct result of many years and great efforts of different international forces, because the war at hand is not only military in nature, it’s also deeply ideological.

In order to overcome the power that has been built by the peoples of this region, the heart of the revolution—the democratic nation and the brotherhood of peoples—must be attacked and destroyed.

This is the result of an effort of many years by both Turkey and HTS in Syria. Long before the fighting even began, the tribes of Syria were being influenced and won over by the Turkish and the Islamic fundamentalist forces in preparation for this exact moment of defection.

For years, the Turkish backed mercenaries of the Syrian National Army (SNA) have also been incentivized to work towards this goal of increasing unrest in different areas controlled by the SDF, with the goal of detaching Arab tribes from the autonomous administration and to instrumentalize them against other social groups such as the Druze in Sweida.

In 2025 there was a large delegation of Syrian Arab tribal leaders, to Turkey. This was followed directly by talks in Raqqa, in Deir Ezzor and in Ras al-Ayn. The goal was restoring trust

with Turkey. Jolani welcomed Turkey restoring trust with the Arabic tribes, convincing them to cooperate with HTS and dissuading them from cooperating with the SDF and the autonomous administration. The STG itself also set about cultivating a relationship with the Arab Tribes. There is a specific office in the STG, the Advisor to the President on Tribal and Clan Affairs, in it a man named Jihad Issa al-Sheikh.

So once the STG took power, they began to win over some of the Arab tribal forces in Aleppo, for example, who had previously worked with the SDF. This served as kind of a test run for what would soon happen east of the Euphrates. The ground had already been laid for the mass defection, with much effort from Turkey and from the STG.

But this begs the question: why did these regions defect seemingly so quickly? We need to understand the historical context. The regions that these Arab tribes were coming from were places that were much more recently liberated from ISIS. They were not parts of the regions of North and East Syria, where there had already been decades of underground work and organizing that had been done in order to prepare the soil for the Rojava revolution.

So these were not only regions who did not have the institutions of the women’s movement or democratic communes being built up. They were also regions that were very strategic and ideological centers for ISIS’ caliphate. We all know that Raqqa, for example, was the caliphate’s declared capital. Once they were liberated from these jihadist forces, the regions and the cities were still in the very early stages of learning women’s autonomy and self determination.

I mean, I can say, even from my own experience, walking in the streets of Tabqa and Raqqa was nothing like walking in the streets of Qamishli. There was severe oppression, no longer by the military force of ISIS, but by way of mentality. Many, if not most, of the women were still fully covered. There were still cells of ISIS that were breaching the walls of our military base on the Euphrates River almost weekly. ISIS was still very, very present in this society.

It wasn’t yet a place of revolution. It was in the beginning phases of lifting away the very heavy hand of fundamentalist Islamic oppression. The people did not yet fully understand that they no longer had a ruler, that in order for society to function, they must actually participate in their local communes and councils. They were approaching and treating SDF as if they were a new military occupier, and they were afraid of participating.

The women’s movement and women’s structures especially took a lot of time and effort to be built up there. It was very hard to convince the people of the ideas of women’s freedom and autonomy. For example, women from other parts of the North and East would come to give lessons. They would give seminars about women’s rights. They would give seminars about women’s liberation, maybe something about Jineoloji.8 These were civilian women, they weren’t coming from being many years in the movement. These women would come and stand up in front of 10s of men. There were no women, because women were not yet allowed by their families to come and see this type of education.

And the men would not listen to the woman who was speaking to them. They wouldn’t allow her to teach. Because, according to their mentality it’s disgraceful for a woman to stand up in front of men and speak to them. So how did the movement overcome this? Women who had been in the movement for a much longer time, women who were coming from experience in the PKK, would come and they would start giving lessons to the men, the local men, and the men would listen to the PKK women.9 The women would stand up in front of the men, without a headscarf, without anything, and the men would have respect for these women, whatever kind of respect that means.

So then what the PKK women would start to do is, within each lesson, they would take one of the local women who were originally supposed to give the lessons, they would take them up for five minutes and let them speak in front of the men, and then they would sit back down, and they would continue the lesson. And they did this for longer and longer until it became normalized that the local women could stand up in front of the men and speak, until they could finally give entire lessons to these men.

So this is the kind of very, very slow process that I’m talking about, of changing oppression is not just changing the force that is in control of a region. Given this mentality and the kind of power that the tribal leaders still wielded over this part of the society, HTS did not need to convince tens of thousands of people—they only needed to convince the tribal leaders to defect. With them would come everyone under with loyalty to the tribe.

We should be clear that this situation did not arise because people were not accepting of the Autonomous Administration because they were somehow oppressive. Instead, the politics at play here, were very much being manipulated in the politics of HTS and of Turkey.

Of course, there is a truth, and there is a complexity to the situation, about the defection of these tribes because they never wanted a new force in the region, and much of the rejection of this force is also fueled by racial chauvinism or religious chauvinism. They don’t want to be, as they see it, occupied by the Kurdish people, especially by types of people that have very different religious beliefs from them.

So this tension has seen efforts of many years of manipulation by Turkey, by HTS in order to fuel these hostilities, because the weakening of the revolutionary project, the weakening of the Kurds, the weakening of the Arabs, the separation of different ethnicities in order to dominate the Middle East is a 200 year old policy of divide and conquer, which has directly helped to maintain the hegemony of capitalist modernity In the Middle East.

IRC: Can you describe how you, as someone who has participated in the structures of the revolution, are relating to the situation?

IRMA: So when things started to become more intense, when the siege started in Aleppo, for example, I was actually in Europe. I was doing a tour. I was visiting different women’s institutions and people’s institutions, and different projects that both the movement had built up over time, but also projects that were building people’s power and creating little pockets of revolutionary force. I was visiting a lot of them just to see how they were working, what kind of challenges they were having.

At the time, I was in Germany, and a friend had actually brought us to this local bakery to enjoy some cake. So we were sitting in this bakery, and as we were eating one of us was scrolling on the news, and she told us that the war had started. I remember how in that moment all of us stopped eating, and the cake just turned to ash in our mouths. It was just this moment of really utter despair.

Even so, I think for Europe in general, it took some time for everyone to fully understand the gravity of the situation, including us, that the siege and the deaths in Aleppo were also a precursor to something much bigger. When this fully started to be understood, that mass mobilization really began, it was mostly by the Kurdish communities that were in Europe.

Those in the U.S. may be aware, but there is very large Kurdish diaspora in Europe. Because of this, the Kurdish freedom movement has been present there for decades, the communities are quite strong and quite organized. In many countries, there are women’s organizations and diplomatic institutions and many projects of building people power in the society.

Because of this, the response to the current situation was quite big. In every city, there were marches, there were huge demonstrations. As I was still making my tour, as I was still moving around Europe, from Germany to Belgium to Switzerland, each place I went to, the local people would tell me that they have never seen this kind of turnout or energy for a demonstration at this city before.

It wasn’t all positive. There was a lot of pain, you know, watching all together every day, the events unfolding and so quickly. Eventually, it manifested as this feeling of desperation, really coming over everyone. And I think that feeling of desperation was also really manifesting in some of these demonstrations, like they were becoming a bit wild, some of them.

We were searching for anything to do, any kind of action to take. We needed to do something, anything. So, of course, anytime there was a march, anytime there was any kind of solidarity action, we would be there. I went from city to city, going to these marches, and it was never really enough.

What we needed was some kind of action that would be effective. But because things were happening so fast, there was really such a lack of clarity of what is the right thing to do. So eventually we decided to sit down, to strategize. When I say we, I mean many, many women from different organizations, not necessarily representing any kind of affiliation, but women who had a connection to the Kurdish Freedom Movement had a connection to the ideology of a democratic nation and women’s liberation ideology.

We stayed up all night, and the proposal of the People’s Caravan was born from this.

And so we decided, some of us would go directly to Rojava to join the resistance. This meant different things. Whether it be military, whether it be medical, whether it be through media works, really anything that is needed there on the ground.

The second way is that many people would go directly into Amid or Diyarbakir [in Turkey], and make legal and media pressure. This was very much inspired by the delegations that go during the elections in Bakur [Northern Kurdistan/Turkey] who go to observe to prevent corruption. The friends who chose this path were just yesterday detained by the Turkish police, and they were deported from Turkey.

The last branch of this project would be the caravan itself. The caravan action would be all across Europe, picking up cars of internationalists along the way in order to reach the other side of Kobani, which is under siege, in order to break down the borders, open up the city to humanitarian aid and be part of the defense of the city of Kobani.

Just earlier today, the caravan finally reached Suruç, which is the town border of Kobani in Bakur [Turkey/Northern Kurdistan]. They’re participating now in the demonstrations there.

Participants in the People’s Caravan to Defend Humanity arrive in the Turkish city of Suruç, bordering Kobani, to participate in pro-Rojava demonstrations there.

Video Credit: People’s Caravan

A friend made this comparison and I did find it very appropriate, that the People’s Caravan initiative is very similar to the flotillas to Palestine. I mean, actually, some of the artists that were helping us with the designs were the same ones who are doing work for the flotillas. So there’s definitely a connection there.

If people want to follow the situation, they post a lot of updates on their instagram, their website, and their telegram channel. I would highly recommend that anyone in the US interested in the situation in Syria generally download telegram for news updates.

I would like to say that having some kind of direction, having a big project like this can really help in these types of times and situations to motivate people towards action.

I think having a proposal like this that people can come and join, is really important to make some kind of mass mobilization, to make something very big, As well, on a personal level, as everything was beginning to happen in Aleppo I was feeling very frazzled, and I was very unclear, I was very emotional. But once we came up with a strategy, once we came up with an action, a direction, things became very clear, and the path forward opened up. And also things looked achievable.

It really affected our morale, and even affected the way that we perceived the situation and had analysis of the situation in Rojava. We could see a way forward, we could see a future once we began to take action.

So I really urge anyone right now who is feeling very overwhelmed, not just with the situation in Rojava, but with everything going on in the world: don’t act as a single person. Get together with your friends, your comrades. Discuss together what could be done, what is needed. Be very creative. See yourself as someone with a duty, a task, but the only way that this can be filled is collectively. Don’t do things randomly out of desperation. Approach your activity with hope, with morale, and always work with a philosophy on the foundation of life and freedom.

BRRN – IRC: We’ve been conducting this interview over several days and the situation seems to have changed again as of January 31st. Could you briefly describe the ceasefire deal that has been reached?

What is stipulated for the Autonomous Administration and SDF and what are the implications for the revolution?

IRMA: Things are changing very quickly. Most recently, there was an agreement made for a cease fire between the SDF and HTS. This includes the gradual integration of political, administrative, and military structures of both sides into one unit. It also includes agreements for Kurdish rights, language education to be insured, as well as the return of internally displaced people back to their homes, including places like Afrin.

Before I go further, I want to preface this topic with the fact that this agreement will only take place within the context of a successful ceasefire. Because, while an agreement has been reached, the siege on Kobani still continues. There’s humanitarian crises still underway in other areas, and until now, we haven’t seen HTS keep their word on a single ceasefire that has been agreed to.

It is crucial to communicate that what we are seeing happen now is a military struggle moving into the arena of a political struggle. We really must not be disheartened or come to any major conclusions about the fate of the revolution based on this one agreement. The struggle for autonomy in this region has been, and will continue to be, a decades long struggle.

So I would really encourage everyone to look deeper into the agreement. A great place to start would be the interview given by Îlham Ehmed on the topic. Anyway, once we can hear everything that the agreement entails, we can really imagine better in which areas the power dynamic has been changed, and what it might actually look like and what it might actually mean.

Because the short headlines make it sound very scary, as if the entire social revolution is over with. But when you read into the details, it definitely does not mean the surrender of the autonomy of the region.

For example, some of the points include military integration. This means that Damascus security forces are being deployed into the city centers of Hasakah and Qamishli. However, this is impermanent. They’re only doing it for a short time period in order to oversee the integration process and then they will leave again.

There’s also going to be a military division built up in Aleppo, which consists of three brigades affiliated with the SDF and one brigade from Kobani.

Lastly, and most significantly, is the integration of the Autonomous Administration’s institutions into Syrian state institutions.

Something that is really emphasized is that the existing military structures of the SDF will be and not dissolve, that local administrations and internal security forces will remain under Kurdish control. So in other words, the achievements by the Kurds that have developed so far in this way will be protected.

Similar to the way that many people made sweeping judgements and had big reactions to the dissolution of PKK, we are seeing people come to really big conclusions really quickly based off of this agreement that we also still don’t fully understand.

At the same time, given what is available about the agreement, I can’t pretend that this doesn’t sound like a loss. I do think it’s a lot more complex than what some are saying, which is, that it’s over, it’s the end of the revolution. This kind of rhetoric is happening without very much analysis. I think when we look deeper into it, we can, we can see that there is within this situation, opportunity, similarly to the disillusion of the PKK, there is opportunity for transformation, which is part of this longer term strategy of the freedom movement, which I spoke about earlier, which is to democratize the other elements of Syria, democratize other elements of the Middle East and eventually larger parts of the world.

The SDF and the Autonomous Administration, they’re not only integrating into the government of Damascus, but also elements of the government of Damascus are integrating into the Autonomous Administration. This is an opportunity to be able to affect these forces and push them to accept greater levels of freedom.

Of course, this is going to be something very difficult. This is the diplomatic line coming from the Autonomous Administration as it is moving away from the line of revolutionary struggle.

At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that the Rojava revolution is not only made up of these diplomatic forces. For example, the revolutionary women’s institutions will never stop working towards women’s liberation in all forms, the revolutionary youth—sometimes the most radical and the most fiery forces of the revolution—will never accept surrender to the state.

So now that the military conflict is transforming into a struggle of the political arena.

We need to watch and participate with as much vigilance as we have so far in this military conflict, because the war is not over, and we see that with this agreement.

For example, The Syrian Democratic Council has said, what’s happening today in Syria is not the end of the road, but rather an opportunity for transformation.

It added that this opportunity requires all democratic forces to reassert their roles. This isn’t just diplomatic talk. This is them saying, to us, me, and you, the democratic and revolutionary forces of the world, we must take up our responsibility and play a role in this political struggle in the form that it’s taking now.

So this is also why internationalism is so important in these moments, peoples from different places, thinking and working in the long term, building power against the imperialist system.

Because now Rojava has no more tactical allies. Rojava now only has strategic allies, only has revolutionary allies. And if we are not strong enough to be that ally for Rojava, then we also have to think about for ourselves, how much can we actually criticize this agreement and what’s happening right now? How much of a role did we play in this situation, and what can we do to also fix it?

So taking up our own tasks, in our own locales, to become powerful enough to affect the situation is part of our responsibility as internationalists.

BRRN – IRC: For those here in the United States feeling the kind of desperation you described earlier, what do you believe can be done to have an impact on the situation, however minor?

IRMA: There’s no formula. But, we can start by thinking about these types of situations in different ways. We can think about what is needed in the short term, what is needed in the mid-term, and what’s needed in the long term.

In the short term, we need to make a fucking racket. We need to make a spectacle about what’s going on. Everyone needs to know about what’s going on. There should not be a single person whose life is continuing as normal when this revolutionary project is under attack, because this revolutionary project is all of our revolutionary projects. It is being built up by the hands of the people in this region.

So I think consciousness building, making actions, joining mass mobilizations, organizing mass mobilizations, sending out solidarity messages. I mean, even just the morale that can be built up by the people that are facing the struggle right now, knowing that the world is watching them and that we are with them. All of these are relevant.

Media, I think, plays a special role. We are living in an age of media. We need to know very well how to use Tiktok, how to have people listen to us. You know, back in the day, it used to be standing on street corners and becoming a master of oratory. Now it’s the age of Tiktok.

I think even larger, what we can be doing is using people power to make demands. That requires really organizing people together and not just having demonstrations. Rather it means bringing people together in a more intense way to do things like occupy buildings, sit on railroad tracks, and be seriously disruptive toward the end of demanding formal recognition of the North and East.

Part of our responsibilities as leftist, radical, revolutionary people coming from, specifically the United States, is the absolute necessity of destroying US imperialism. This is part of our revolutionary task, because when we can do this, we will affect all of the other revolutionary projects of the world drastically. We will affect the ability for people to become more free.

So in this sense, actually putting a lot of our efforts right now into radicalizing, organizing around the situation, around ICE, this is actually something that I would really urge us to put all of our efforts into. It’s our task to organize the people who are right now fully mobilized. We have to turn the insurgent force of the people into people’s power. Transform it into power that can stop the functions of society, to turn the general strike of one day into the general strike of a week, into the general strike of a month, into the national general strike that persists, until we can defeat and transform the federal fascist violence that we’re facing.

When it comes to long term, what we can do to actually be the best allies, the best comrades to the people of Rojava is actually to build up these types of independent, democratic, and women’s liberatory projects in our own places, becoming another revolutionary force in the world. Combining our fronts—from Chiapas, to North East Syria, to the Philippine jungles—we can create a network of all the democratic forces in the world. This is something that is going to have to challenge imperialism. This is something that is actually going to threaten the force of imperialism that is dominating the globe.

So the best way that we can actually be comrades to any of the peoples in the world that are facing the threat of annihilation, for being a socialist, for being an anarchist, for trying to create freedom, is also by doing the same thing ourselves. We have to build up in ourselves our own revolutionary character.

We have to come together with our comrades around us and actually become organized. And I don’t just mean forming groups and having these kinds of individual associations, but actually becoming organized, being responsible to each other, organizing your life around the goal of creating freedom, building up a holistic, a comprehensive ideology for yourself and for the people around you, according to your own sociology, your own history, your own geography.

We need to become better, bigger humans, revolutionaries, in order to be better comrades. So on the one hand, international solidarity is very, very important. But in the longer term, we have to ourselves become better revolutionaries and create our own revolution in order to if we ever want to support, if we ever want to help or have an impact, a big, lasting impact on the situation in Rojava.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more on the situation in Syria, we recommend the following articles: We Are Not Pawns, We are the People Who Rose Against the Regime and Statement from Tekoşîna Anarşîst on the Fall of the Regime in Syria: “We Carry a New World in Our Hearts”.

Notes

- Often translated as ‘the science of women’ or ‘women’s sociology’, Jineoloji can be understood as a form of revolutionary feminism concerned with the social scientific study of the conditions faced by women under patriarchal domination and what women’s liberation from such conditions might look like. ↩︎

- Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham is a fundamentalist Sunni Islamist organization that emerged out of al-Nusra Front, another hardline Islamist militia which operated as the Syrian subsidiary of the international al-Qaeda network. Ahmed al-Sharaa, the president of the Syrian Transitional Government served as the military leader of HTS under the nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Jolani. ↩︎

- Throughout this text Irma uses Jolani, al-Sharaa, and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) interchangeably to refer to the and Syrian Transitional Government (STG), the body now in control of the Syrian state after the government of Bashar al-Assad was overthrown in late 2024 after more than a decade of civil war. ↩︎

- Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) is the umbrella term for a number of militias under the command of the Autonomous Administration in North East Syria. It includes well known militias such as the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), as well as lesser known allied militias such as the Syriac Military Council. Prior to their mass defection, SDF also included a number of Arab tribal militias, a topic discussed later in this interview. ↩︎

- Democratic Nation is a political concept developed by Abdullah Öcalan, imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). An elaboration on the concept can be found in his book on the topic. ↩︎

- Here Irma is referring to the process of negotiation between Turkey and the PKK, which has led to the latter’s dissolution in favor of struggling by other means. ↩︎

- Mazloum Abdi is the commander of the SDF. ↩︎

- See footnote 1. ↩︎

- The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) was founded in 1978. Before its dissolution in 2025, it waged a decades long campaign of guerilla warfare on the Turkish state. ↩︎